HEP Case Study: The Rubin Observatory and the Images Sent Around the World

By Sara Harmon, media@es.net

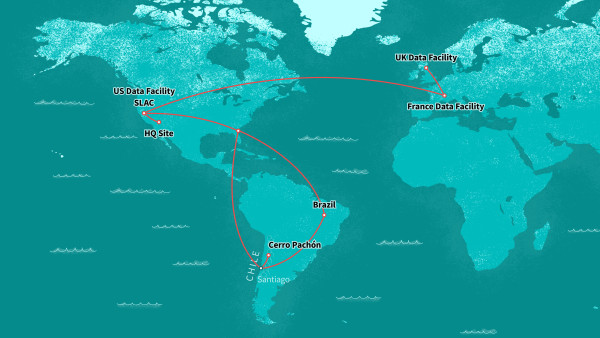

Illustration of Rubin Observatory data centers shown on a world map. Credit: Rubin Observatory

This article is part of a package about the ESnet HEP 2024 Requirements Review report, released on Oct. 1, 2025. The report details ESnet’s engagements with network users from the Department of Energy’s Office of Science High Energy Physics program and the process of assessing how the network meets, and will evolve to continue to meet, the data-heavy demands of modern scientific research. This is a synopsis of the Vera Rubin Observatory case study; see also the DUNE experiment companion case study.

![]()

In June 2025, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, captured its first images, using the largest digital camera in existence. Jointly funded by the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy, the facility will run for about 10 years with a mission of mapping the galaxies to “understand the nature of dark matter and dark energy, inventory the Solar System, map the Milky Way, and explore objects that change position or brightness over time.”

These stunning images are just the beginning of a “sky-breaking” data collection that will be utilized by astronomers and astrophysicists around the world. Each night, the 8.4-meter (~27.5-feet) Simonyi Survey Telescope captures approximately 20 terabytes of data, with about 500 petabytes expected over the course of the study. That’s about 62.5 million high-definition movies’ worth of data.

The incredible resolution of these images is more than aesthetically pleasing — it is key to the project’s mission. From its position atop the Cerro Pachón mountain in central Chile, the telescope surveys the sky each night, capturing several images. Those terabytes of data must traverse the 12,000-mile, continents-spanning Long-Haul Network in under 7 seconds to the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory at Stanford University in California, where the images are digitally compared with those from previous surveys. If a difference between two images is detected, an alert is sent out to the research community across the world, so other observatories and telescopes can be activated to investigate the differences. For this to be scientifically useful, the entire sequence must occur within 2 minutes from the moment the camera shutter closes.

This feat of data transference is an extraordinary effort in collaboration among multiple network organizations across several international borders. The participating networks include REUNA, the NREN of Chile; RedCLARA, the regional R&E network for Latin America; the NSF-funded Americas-Africa Lightpaths Express and Protect (AmLight-ExP); RNP, the NREN of Brazil; rednesp, the NREN for the State of Sao Paulo; Florida LambdaRail, the regional network of Florida; ESnet; and Internet2.

The data transfers to the ESnet network in Georgia via the AmLight network, and ESnet carries it to the data facility in SLAC; it also handles the alert transmission. If there happens to be a network issue interfering with the primary route, there are multiple alternatives to ensure that the data gets to SLAC and beyond within the necessary time frame. At the conclusion of the ten-year Rubin Observatory Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), the Long-Haul network will have transferred more than 800 images of each location in the sky.